MOA vs MRAD: Understanding Minute of Angle and Milliradians

Two different methods of measuring angles are MOA (Minute of Angle) and MRAD (Milliradian, often just called “Mil”) These will allow you to adjust your rifle scopes and estimate range. If those terms sound intimidating, don’t worry! Think of them as the “inches vs centimeters” of the shooting world – two units for measuring the same thing. In this guide, we’ll break down what MOA vs MRAD means in simple terms. Talk about scope adjustments and range estimation. The pros and cons of each, and how to choose the right system for your needs. We’ll use friendly language, real-world examples, and even a few analogies so all shooters – from beginners and hunters to competitive long-range shooting – can grasp the concepts easily.

What is MOA (Minute of Angle)?

Minute of Angle (MOA) is simply a unit for measuring angles. Just like there are 60 minutes in an hour, there are 60 “minutes” in one degree of a circle. And since a full circle is 360 degrees, that means there are 360 × 60 = 21,600 minutes in a circle. A minute of angle is one of those small slices of the 360° pie.

- Handy rule: 1 MOA covers about 1 inch at 100 yards. For us shooters in the US, this is the most convenient measurement to use. In fact, 1 MOA is equals 1.047 inches at 100 yards, but for simplicity reasons, we just use one inch. That means if your shots are hitting 1 inch apart at 100 yards, that’s about a 1 MOA group.

- Scaling with distance: Because MOA is an angle, its effect grows with distance. At 200 yards, 1 MOA spans roughly 2.094 inches (about 2 inches), at 500 yards – 5 inches, etc. In other words, the farther the target, the larger the spread that 1 MOA covers. This linear growth is handy: for each additional 100 yards, add roughly another inch per MOA. So, 5 MOA at 100 yards is 5 inches, and at 300 yards that same 5 MOA would be 15 inches.

- Why it matters: MOA is used to describe accuracy and adjustments. If a rifle is advertised as sub-MOA, it means it can shoot groups smaller than 1 inch at 100 yards. If your rifle is shooting 2 inches high at 100 yards, that’s about 2 MOA high, so you’d adjust your scope accordingly. MOA gives us a common language to talk about how far off a shot is and how to correct it.

What is MRAD (Milliradian)?

Milliradian (MRAD or “Mil”) is another unit for measuring angles, just a different system. Instead of dividing a circle into minutes, the mil system comes from the radian. There are 2π radians in a circle, which works out to about 6.283 radians in 360°. So each radian is about 57.3°. To get a more useful unit for shooters, each radian is divided into 1,000 milliradians. So a full circle has 6.283 × 1,000 ≈ 6,283 milliradians (often rounded to 6,283 or 6,400 in some military applications). A milliradian is thus 1/1000 of a radian – again, a small angle.

- Handy rule: 1 MRAD covers about 3.6 inches at 100 yards. In metric terms, 1 mil covers 10 centimeters at 100 meters. Mil is short for millimeter per meter , so one mil equals one meter at a 1,000 meters or one yard at 1,000 yards. So at 100 yards, one mil is 1/10th of that amount (~3.6 inches). For example, if your bullet impacts 3.6″ low at 100 yards, that’s a 1 mil drop. At 100 meters, if a bullet hits 10 cm low, that’s 1 mil.

- Scaling with distance: Like MOA, the mil is an angle that scales up linearly with distance. At 200 yards, 1 mil is about 7.2 inches. At 1,000 yards, 1 mil is roughly 36 inches (3 feet). You can calculate it easily: since 1 mil is 1/1000 of the distance, at 1,000 yards 1 mil = 1 yard (36 inches), and at 1,000 meters 1 mil = 1 meter. This consistent 1-to-1000 relationship makes mils handy for mental math.

- Nothing “metric-only” about it: Although MRAD comes from the metric system (radians) and is friendly to metric units, you can absolutely use MRAD with yards and inches, too. The math stays consistent as long as you use the same units for distance and target size. (For example, a mil is 1 yard at 1000 yards just like it’s 1 meter at 1000 meters.) So while mils are popular globally and with metric users, they’re not limited to metric – they’re just another unit of angle. In practice, many American shooters use mil scopes and simply remember that 1 mil ≈ 3.6″ at 100 yards.

How Scope Adjustments Work (MOA vs MRAD)

When you turn the dial (turret) on a scope to adjust for elevation or windage, you’re moving the reticle by a tiny angle. Scopes are built either in MOA or in MRAD, meaning they click in those units. Importantly, scopes do not adjust in inches or centimeters directly – they adjust in these angular units. Here’s how it breaks down. For a more in depth look, read our full guide on Sighting in your Scope.

- MOA-based scopes: Most commonly adjust in ¼ MOA increments per click. With ¼ MOA clicks, each click moves the point of impact about 0.25 MOA. In real terms, that’s about 0.26 inches at 100 yards per click (since 1 MOA ≈ 1.047″ at 100 yards. It takes 4 clicks to make 1 MOA of adjustment (4 × 0.25 MOA = 1 MOA), which translates to ~1 inch at 100 yards. On your turret you’ll often see markings like “1 click = ¼ MOA”.

- MRAD-based scopes: Most adjust in 0.1 MRAD (one-tenth mil) increments. Each click is 0.1 mil, which moves impact by about 0.36 inches at 100 yards (because 1 mil ≈ 3.6″ at 100 yards, and one-tenth of that is 0.36″). It takes 10 clicks to make 1 full mil of adjustment (10 × 0.1 = 1.0 MRAD), which would move the impact ~3.6″ at 100 yards. Turrets are often labeled “0.1 MIL per click” or similar.

- Finer vs coarser adjustments: Because 0.25 MOA is a smaller increment than 0.1 mil, an MOA scope allows finer granular adjustments. For example, at 100 yards one click of ¼ MOA moves ~0.26″, whereas one click of 0.1 MRAD moves ~0.36″. If you’re zeroing in on a very small target, MOA adjustments can nudge the impact in slightly smaller steps. Most shooters won’t notice a huge practical difference in accuracy due to click size, especially at typical distances. Both systems let you dial in your scope precisely. So it’s a bit like choosing between a ruler marked in 1/16 inches versus one in 1/10 inches.

- Turret and reticle matching: Modern scopes often come in matching units. Meaning if the turrets adjust in MOA, the reticle’s hash marks are in MOA as well (and likewise for MRAD). This is important so that if you see a correction through the reticle (say a shot hit 2 MOA low), you can dial 2 MOA up on the turret directly. Always try to get matching reticle/turret units. In the past, some scopes had mixed systems (mil-dot reticle with MOA turrets, etc.), which required conversion and could confuse shooters. As long as your scope’s reticle and knobs use the same language (both MOA or both MRAD), you’ll be able to adjust without doing any unit conversions in the heat of the moment.

Pros and Cons of MOA vs MRAD

Both MOA and MRAD will get the job done on target. Neither is more “accurate” for shooting – they’re just different units of measurement. That said, each system has some advantages that might make it a better fit depending on your preferences or shooting activities. Let’s compare them:

MOA – Pros:

- Intuitive for standard measurements: Because 1 MOA is so close to 1 inch at 100 yards, it’s easy for shooters used to yards and inches to visualize adjustments. For example, you can think “I need to move 2 inches at 100 yards, that’s ~2 MOA.” This practical relationship holds at other distances (roughly 1″ per 100 yards) making MOA easy to grasp for many.

- Finer adjustment: The common ¼ MOA clicks allow very fine adjustments. At 100 yards each click is about a quarter-inch movement – great for zeroing in precisely on small targets. In fact, MOA scopes are a bit more precise per click than 0.1 mil scopes (0.25″ vs 0.36″ at 100 yards). For disciplines like benchrest shooting at shorter ranges, that finer adjustment can help when you’re chasing small hole groups.

- Widely available and used: MOA has been around a long time and is extremely common, especially in the United States. Most off-the-shelf hunting scopes and many target scopes use MOA. If you grew up shooting/hunting, chances are your scope and the ones your family used were in MOA. There’s a huge selection of MOA-based equipment and many people understand it.

MOA – Cons:

- Less convenient for metric thinkers: If you think in meters or centimeters, MOA can feel awkward. The unit doesn’t convert in a nice round way to metric (1 MOA at 100m is ~2.9 cm). So MOA is favored mostly in places that use yards/inches. It’s not a big deal, but it’s a factor – you might be doing more converting if mixing systems.

- Bigger numbers at long range: Because 1 MOA is a small slice, shooting long distances means dialing larger numbers. For instance, dialing 20 MOA up for a 1000-yard shot is common – that’s 80 clicks on a ¼ MOA scope. The number “20 MOA” is not hard by itself, but some people find it a little easier to remember or communicate a hold like “6 mils” versus “20.5 MOA”. (This is subjective, but many find mil values are smaller numbers that are quicker to say and note down).

- Math for range estimation: As discussed, calculating range with an MOA reticle involves that funky 95.5 factor. It’s doable, but not as head-smacking simple as the mil’s multiply/divide by 1000. If you’re doing manual ranging, MOA is the slower system for most folks. (With laser rangefinders, this doesn’t matter.)

MRAD – Pros:

- Easy math & communication: The mil system’s foundation is based on 10 and “per-thousand” makes mental calculations straightforward. Adjustments and holds often end up being tidy numbers like 2.5 mils, 6.0 mils, etc., rather than, say, 9.5 MOA or 14 ¾ MOA. Many shooters find mils easier to communicate with others: e.g. “hold 1.2 mils left for wind” is direct. In fact, competition and military shooters often prefer saying “mils” because it’s concise and all in decimal form. The numbers are smaller; for the same adjustment, the mil value is about one-third of the MOA value (since 1 mil ≈ 3.43 MOA).

- Fewer clicks for large adjustments: Each 0.1 mil click is a bit coarser, which means to move a bullet impact a given distance, you’ll typically turn the turret less in mils. For example, dialing 1 mil of adjustment (which is 10 clicks) moves the bullet ~3.6″ at 100y, whereas to move 3.6″ with ¼ MOA clicks would take 14 clicks (about 3.6 MOA). This isn’t a huge time-saver, but when you’re dialing up a lot of elevation (say for a 1200-yard shot), a mil turret might require fewer full rotations. Some shooters simply like that the turrets “travel” a bit less for the same correction.

- Standard for long-range and tactical shooting: The military and most top-tier precision shooters have largely adopted mils. This means if you plan to shoot PRS (Precision Rifle Series) matches or work with a spotter, knowing mils is advantageous. Your spotter might call “0.5 mil high” and if your scope is in mil, you can directly dial or hold that. Also, many of the high-end scopes and latest reticle designs (Christmas-tree style reticles, etc.) are in MRAD. The industry tends to focus new tech slightly more on mil scopes, so options for advanced long-range optics are plentiful in MRAD. (Though MOA options exist too.)

MRAD – Cons:

- Slightly less finer adjustments: As noted, the common 0.1 mil clicks jump a little more per click (~0.36″ at 100y) compared to ¼ MOA (~0.26″). For most, this difference is negligible – it’s like the difference between trimming a group by a quarter-inch vs a third-of-an-inch at 100 yards. But if you’re an extreme precision shooter (e.g. benchrest competitor shooting tiny groups), you might appreciate the smaller step of MOA clicks to truly dial to perfection.

- Learning curve for imperial-only shooters: If you’ve always thought in terms of “inches at so many yards,” switching to mils might initially feel strange because the relationship (3.6″ at 100y per mil) isn’t as round as 1″ per 100y. It’s a new mental yardstick to get used to. However, once you train with it, it becomes second nature (and you can always carry a small cheat sheet for conversion until it clicks for you).

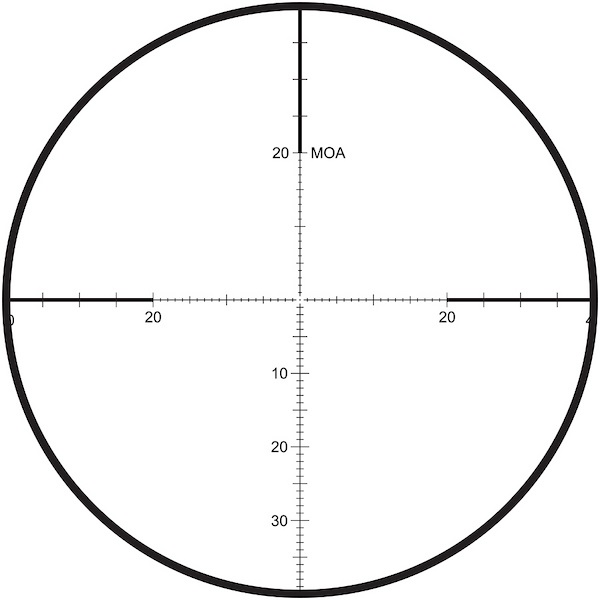

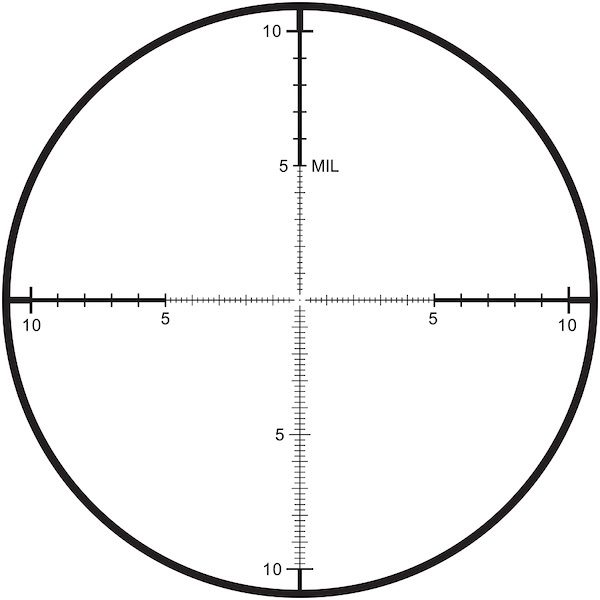

- Less common in hunting scopes: While this is changing rapidly, a lot of hunting scopes in the U.S. still use MOA. If you’re the only person in your hunting camp with a mil scope, discussing shot placement in the field (“that buck is 1 mil in the scope” or “hold 0.2 mil high”) might get you some blank stares. Again, this is changing as new generations of hunters adopt whatever is available, but MOA has been the dominant language in many hunting communities for decades. Below is a comparison of the same reticle in MOA vs MIL.

Choosing Between MOA and MRAD: Tips for Different Shooters

So, which one should you choose? The answer really comes down to personal preference and application – what feels intuitive to you, and what kind of shooting you plan to do. Here are some tips for different types of shooters:

- If you’re a beginner or casual shooter: Either system can work for you. If your friends or mentor all use MOA and talk in inches, going MOA might help you learn faster. Conversely, if you’re starting fresh and plan to watch a lot of modern long-range tutorials (many of which use mils), you could start with MRAD. The key is to stick with one and learn it well first. Both are viable for learning. The priority is a scope with matching reticle/turrets (MOA/MOA or MIL/MIL), not a mix.

- If you’re a traditional hunter (short to mid-range): Most hunting scopes and ballistic charts for hunting are in MOA or inches. If you zero at 100 or 200 yards and maybe hold a couple inches high for a 300-yard shot, MOA is perfectly adequate. In fact, many hunters rarely dial their scopes at all during a hunt – they might use a simple duplex or a bullet drop compensator (BDC) reticle with holdover marks.

- If you’re getting into long-range precision or competitive shooting: Consider leaning toward MRAD. The long-range community (PRS, tactical matches, military/sniper world) largely speaks in mils now. Using MRAD will make it easier to communicate with fellow shooters, read industry-standard ballistic data, and use the latest reticle designs. You’ll also benefit from the easier math when you’re under pressure in a match. Many of the top scopes and reticles are offered in mil configurations with features designed for quick holds and ranging. None of this is to say you cannot compete with MOA – you certainly can, and some people do.

Ultimately, the best choice is the one that you feel most comfortable with and that integrates well with your shooting activities. You can achieve the same precision with either MOA or MRAD once you learn how to use them. It’s far more important to practice reading your turrets and reticle and understanding your ballistics than to obsess over the unit marking those adjustments.

Summary Chart: MOA vs MRAD

To wrap up, here’s a side-by-side comparison of key points about MOA vs MRAD:

| Feature | MOA (Minute of Angle) | MRAD (Milliradian) |

|---|---|---|

| Angular definition | 1/60 of a degree (360° = 21,600 MOA in a circle) | 1/1000 of a radian (≈6.283 radians in 360°, so ~6,283 mils) |

| Size at 100 yards | ~1.047 inches (often treated as 1 inch for simplicity) | ~3.6 inches at 100 yards |

| Size at 100 meters | ~2.9 cm (since 1 MOA ≈ 1.047″ @100 yd, slightly under 3 cm at 100m) | 10 cm at 100 meters (by definition) |

| Common scope clicks | 1/4 MOA per click (0.25 MOA) = ~0.26″ movement at 100 yd | 0.1 MRAD per click = ~0.36″ movement at 100 yd |

| Clicks per 1 unit | 4 clicks = 1 MOA (4 × 0.25) | 10 clicks = 1 MRAD (10 × 0.1) |

| Precision per click | Finer increments (smaller change per click) | Slightly coarser increments (bigger change per click) |

| Adjustment style | More clicks needed for large adjustments (e.g. long-range elevation) | Fewer clicks needed for the same angular adjustment |

| Mental math | Easy for inches/yards (1 MOA ≈ 1″ @100 yd; simple addition per 100 yd), but MOA-based ranging requires a factor (95.5) | Easy for metric (1 mil = 10 cm @100m) and “base-1000” calculations for ranging; simpler one-step formulas |

| Typical use cases | Common in hunting and older scopes; popular in USA traditional shooting. Often preferred for short-to-mid range where fine precision and inch-based thinking matter. | Standard in military/LE and precision rifle competition. Great for long-range shooting, sniper/PRS matches, where quick math and communication are priority. |

| Pros summary | Intuitive inch correlation; very fine adjustments; wide availability and familiarity. | Quick calculations and communication; smaller numbers; fewer clicks for big moves; widely adopted in high-end optics. |

| Cons summary | Larger values for long-range (can be less convenient to communicate); not as metric-friendly; reticle ranging math less straightforward. | Slightly less granular per click; can confuse if you think only in inches (learning needed); historically less common in some hunting circles (legacy issue). |

Conclusion

In the end, MOA and MRAD are just two ways of measuring the same thing: angle. They both allow shooters to make precise adjustments for bullet drop and wind drift so you can hit your target at various distances. MOA might resonate if you like thinking in inches-at-yards, whereas MRAD shines for those who prefer a metric-like, decimal approach (or need the ease of mil-ranging). Neither system will magically make you shoot better without practice, and switching units won’t tighten your groups overnight – it’s all about how you use the system.

For most shooters, the choice can be boiled down to comfort and context. If you’re brand new, pick one, learn it well, and you’ll do fine. At the range, see what others are using and consider matching it for simplicity. If you’re a lone hunter sticking within known distances, MOA is a trusty companion. Want to dive into PRS competitions or dialing elevation at a mile, MRAD is the trendy tool for the job.

What matters more is consistency. Once you choose, stick with your system across your gear to avoid confusion. Over time, adjusting your scope will become second nature, whether it’s “1 MOA up” or “0.3 mil right.” The target won’t know the difference – a hit is a hit! So, use whichever helps you get on target fastest and with confidence. Happy shooting, and may your groups be small (whether measured in inches or centimeters)! Don’t miss this one – Best 2024 Budget Deer Hunting Rifle Scopes to dive into some scopes that will perform without breaking the bank.